ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN FOOD DIVE

The ‘silent salesman’: How kosher certification went mainstream

By Megan Poinski

Right now, Jewish people around the world are scrutinizing their cabinets and pantries, trying to get rid of any food items that aren’t kosher for Passover.

Hanan Products has been ready for this year’s holiday, which runs from the evening of April 15 to 23, for months.

Every January, the New York manufacturer of whipped toppings and creamers converts its entire factory to kosher-for-Passover production for a little more than two weeks.

In an interview in late January, as the special manufacturing period was drawing to a close, Chief Operating Officer Ryan Hanan described the process. Several rabbis were moving around the factory floor, scrutinizing every detail as the factory churned out non-dairy whipped toppings and coffee creamers that can be used during the eight days of Passover. Specialized sealing tape was everywhere. Only one line in the facility was running, and workers spent long hours making the specialized products that the commercial bakery customers Hanan Products serves will need for the annual holiday.

“It’s a little hectic,” Hanan said.

But the hectic time pays off at Passover. This year, Hanan Products made about 250,000 pounds of kosher for Passover items. The company is one of the few in the space that makes a product that can be enjoyed by observant Jews during the holiday. Rabbi Eli Lando, executive manager of certification organization OK Kosher, said that kosher for Passover is an especially hot market because most people in the Jewish faith — not just those who follow a kosher diet on a daily basis — will stick to those products during the eight-day holiday.

Every day of the year, however, kosher is a hot market, period. Research in 2017 by Kosher Network International — commonly abbreviated KNi — found that the global market for kosher foods was worth $24 billion, and was projected to grow 11.5% by 2025. OK Kosher, which is one of the largest kosher certification organizations in the world, has certified around 700,000 products made by 4,000 manufacturers, Lando said. Its clients include Kraft Heinz, Kellogg and General Mills.

Kosher is one of the most popular certifications in the food industry today. According to one commonly cited estimate, the certification is on about 40% of all products in a U.S. grocery store.

While there are about 6 million Jews in the United States, according to World Population Review, Lando said Jewish people represent only 20% of the kosher product consumer base. By and large, consumers see a kosher certification as a verification that a product is healthy, clean and safe. And while the certification has roots in religious traditions that are thousands of years old, it now speaks directly to the modern consumer’s demand for wholesome foods.

What is kosher?

In essence, food that is kosher adheres to specific dietary laws for members of the Jewish religion. Different religious texts and their interpretations lay ground rules about the types of food items and ingredients that observant Jews need to eat, as well as which foods and ingredients they need to avoid. Some of these rules involve not cooking meat and dairy together and only consuming products from animals that are kosher — generally cloven-hooved mammals that chew a cud, certain birds, and seafood with scales — and killed and prepared according to kosher rules.

In the days before widespread CPG food and drink manufacturing, it was relatively easy for observant households to be able to make choices based on those dietary laws, said OK Kosher Project Coordinator Ilana Klein.

As CPG-style food became more popular, different ingredients, additives and processes changed the ultimate composition of food and drink. It became much more difficult for individual consumers to know whether items met with their dietary laws. So, Klein said, kosher certification groups formed to visit manufacturing facilities, scrutinize and study ingredients and offer advice to CPGs and consumers about which foods, processes and ingredients were kosher.

OK Kosher has been certifying food products since 1935, and is one of the larger certification organizations today. The ingredients and manufacturing processes for every product that has the organization’s circled K on its packaging have been scrutinized by OK Kosher’s staff of experts. In addition to all of the CPG products OK Kosher has verified, Lando said there are more than 1 million ingredients that the group monitors.

“Any certification worldwide has their standards based on regulations that were developed by mankind, people who have come together and decided that this would be the standard,” Lando said. “The standard of kosher is the interpretation of the Bible, which has been in Jewish tradition for thousands of years.”

Kosher certification is not about ensuring food is high quality or healthy, Lando said. It attests certain processes related to safety and purity enshrined in Jewish law are followed. And it means that those who work with certification — many of whom are rabbis — continue to make site visits and investigate processes and ingredients.

“Any certification worldwide has their standards based on regulations that were developed by mankind, people who have come together and decided that this would be the standard. The standard of kosher is the interpretation of the Bible, which has been in Jewish tradition for thousands of years.”

Geller, who is known as the “Queen of Kosher” for her presence in Jewish lifestyle media — writing cookbooks, hosting online cooking shows and founding KNi — said that the halo of a kosher certification has deep roots. While it is important to consumers who only eat kosher products all year long, it’s also become synonymous in popular culture for something that is pure and honest. After all, she said, it’s not uncommon for people making any kind of agreement to talk about whether it is “kosher.”

“People have a lot of reverence for a religious set of eyes, which cannot be compromised,” Geller said. “So they really know that whatever is in the package is actually in the package — nothing more, nothing less. And there’s an independent board or body governing that process. That’s why it’s become so much more mainstream.”

Kosher continues to be top-of-mind for both consumers and manufacturers. According to Innova Market Insights, almost a third of all product launches in 2021 had a kosher claim. More than half of all dessert and ice cream launches were certified kosher, and 17% of the new kosher launches came from the bakery category.

Read More in Manufacturing

Roger Horowitz, author of “Kosher USA: How Coke Became Kosher and Other Tales of Modern Food,” said that in this day and age, a kosher certification is almost a need-to-have. Unless a product is something that could never be kosher certified — for example, something containing shrimp — or it would be extremely expensive to create a kosher version — like a budget product that contains meat — the default is for it to become kosher certified.

In kosher we trust

While kosher certification began as a way to tell members of a religious community what they could eat, the symbol means much more to a wider swath of consumers today.

“If the product has a kosher symbol on it, it says … [it is] a company that invests in quality, a company that cares about the product they make,” OK Kosher’s Lando said.

Lando recalls something an attorney told him: Kosher certifiers answer to a higher authority. For that reason, he said, they don’t let things slide. When examining manufacturing facilities, kosher certification groups point out any issues and force the manufacturers to deal with them.

Because of the vital role a kosher certification plays to observant consumers, Lando said that transparency is key. The effect of that transparency, as well as the trust the community places in rabbis, adds to the deference that consumers give the certification.

The popularity of kosher certification is something that has snowballed through the years. Horowitz said that one impetus for manufacturers to get the certification is simply access. There are areas of the U.S. with larger Jewish populations — like the New York City region, as well as several other East Coast cities. Grocery retailers that serve those populations may prefer to put more kosher products on their shelves simply for those customers. And if these stores are part of larger chains, the kosher products will spread to new locations.

Geller said this begins a validation loop for kosher food. As there are more kosher certified products available throughout the store, she said, they become both more prevalent and prominent. The sheer numbers, she said, increase demand among consumers.

Kosher also has the connotation of being healthy, Geller said — though the certification has nothing to do with nutritional qualities. Kosher certifications are usually next to the other labels and symbols that show a product’s nutritional and ingredient qualities, such as “vegan friendly,” “organic,” “all-natural” or “gluten-free,” providing the association.

Kosher certification offers other helpful information to consumers, Horowitz said. If a consumer is lactose intolerant, for example, kosher certification can indicate whether a product contains dairy.

“People have a lot of reverence for a religious set of eyes, which cannot be compromised. So they really know that whatever is in the package is actually in the package — nothing more, nothing less. And there’s an independent board or body governing that process.”

The 2017 KNi study found that kosher products drive three times larger basket sizes among shoppers, though only 10% of those products come from specialty kosher sections that provide Jewish ethnic food. Geller said the reasoning behind this is two-fold. For consumers eating all kosher food for religious reasons, they follow other Jewish traditions, including weekly entertaining on the Sabbath. This is akin to having a Thanksgiving-style meal each week, she said, inviting friends, extended family and neighbors.

For consumers who have no religious reason to buy kosher food, the ones who pay close attention to the certification tend to be more affluent, Geller said. These people usually buy more at the store anyway, but they are also more apt to pay premium prices for the branded products they most want.

Because kosher traditions date back thousands of years and find their beginnings in a religious, ethnic and cultural community, Geller said that kosher presents a sense of authenticity. As people are embracing more genuine forms of food and drink, items that are kosher fit into that space for consumers.

“They really, really feel that it’s authentic, and from the source and it’s timeless,” Geller said. “…If you want to really learn how to make tomato sauce, I want an Italian grandmother to teach it to me. That’s the idea with kosher food.”

How to be kosher

While hundreds of thousands of products have kosher certifications, the right to bear a kosher seal is something that is hard earned. OK Kosher’s Klein said that the certification goes far deeper than filling out a form and checking boxes.

“It became more and more sophisticated as time went on, and it’s definitely one of the major pioneers in the United States and across the world,” Klein said. “Our organization is constantly upholding the standards, setting the standards, determining new standards, always examining the new technology and new practices.”

Lando said that earning kosher certification through OK Kosher is no different than working with any other regulatory agency. After a CPG manufacturer applies online, OK Kosher discusses product specifics with the company and visits its manufacturing facility. It puts together a certification plan and requirements, and schedules visits to ensure that the manufacturing lines remain in compliance. The manufacturer also signs a legal agreement to use the OK Kosher trademark.

It can take as little as four weeks for a product to get an initial kosher certification, depending on how ready the item and facility are. OK Kosher’s certification lasts a year, meaning all companies are subjected to at least an annual reinspection. However, Lando said, kosher inspectors do make unplanned visits to ensure companies are continuing to follow the proper procedures to maintain certification.

In his book, Horowitz wrote about some of the specific challenges CPG companies have dealt with as they sought kosher certification. Many involved single ingredients that were not kosher. Horowitz said that gelatin has caused problems through the years. The ingredient can be sourced from a variety of places — including red meat, fish and vegetables — but the mouthfeel varies depending on its source. Horowitz said that finding a kosher source of gelatin that does not impact the eating experience has been challenging, especially because the ingredient must be sourced from an animal killed in accordance with kosher law.

“If you’re a large manufacturer making large sorts of products, if you have to disrupt the assumptions and the habits of consumers by changing their product mix by changing the gelatin, it’s not worth it for you to do that,” Horowitz said.

“If you want to really learn how to make tomato sauce, I want an Italian grandmother to teach it to me. That’s the idea with kosher food.”

In the 1950s, Coca-Cola faced a similar ingredient challenge, Horowitz said. At the time, its signature soda contained a small amount of animal-derived glycerin, which is not kosher. However, industrial ingredient producers found that petroleum-derived glycerin is kosher, edible and less expensive than the animal variety, Horowitz said. All of those contributed to Coca-Cola — and other manufacturers — turning to the petroleum-derived ingredient.

Lando advises companies today to go into designing products and manufacturing processes already thinking of kosher certification. If a company has to make big changes in order to become kosher, or if attaining certification gets in the way of doing business, he often counsels them not to do it. For a food manufacturer to make kosher products, the ingredients, equipment and production lines all need to be certified. And it all needs to be kept in order — a non-religious person may not mind if a product with a kosher seal was made on a production line that did not undergo proper sanitization processes, for example, but it means much more to someone who is observant.

Like many trends today, KNi’s Geller thinks that kosher’s popularity has been magnified by social media. Historically, while many large CPG brands have offered certified kosher products for decades, not many had promoted it, and the certification seal itself isn’t especially prominent on packaging. Geller said manufacturers seemed to not consider kosher as an earned certification that every consumer would want to know about.

About 10 to 15 years ago, Geller said, that started to change. The ability to do specific marketing on social media helped drive the realization of how important a kosher certification really is to consumers.

“They started to actually target the kosher customer, and then saw that value expand out to … the international community or those that just see kosher as a symbol of approval,” Geller said. “Then the explosion really happened and the certification went mainstream.”

On KNi, the huge popularity of kosher food is evident. Geller publishes an array of KNi cooking videos featuring different cuisines and cooking styles, in which all of the recipes are kosher. The most popular videos are on KNi’s homepage — with 187.3 million views for a video on Middle Eastern dips, 74 million views for one on the Arabic dip matbucha and 44.2 million views for one on cheese-stuffed falafel.

“There are only 15 million Jewish people in the entire world,” Geller said. “People. We’re talking about men, women, children and babies. And we have videos with over 10 million, 15 million views.”

As far as certifications go, kosher is relatively inexpensive. OK Kosher is a nonprofit, Lando said, and most companies in North America pay somewhere around $5,000 to $15,000 for an annual certification. The cost is based on aspects like the location, number, size or volume of facilities where the food is made and the amount of supervision and monitoring needed based on the product type.

When manufacturers ask what the return on investment is for making a product kosher, Lando responds that they should also consider the “return on ignoring.” He noted that certification costs are a fraction of what a company pays for larger marketing expenses, like a Super Bowl ad.

“If you take off the kosher symbol, you will find out how many customers you chased away, and that is going to be a much more expensive lesson to learn,” Lando said. “…It’s not a mistake that companies large and small, have kosher symbols on their products year after year after year after year.”

Horowitz said studies have shown only about one in 10 consumers seeking a kosher certification on products actually follows a kosher diet.

“You’re talking about millions of people who are looking for a kosher label on products,” Horowitz said. “And if that label can be obtained for a relatively modest cost, then it becomes an asset to the marketing activities.”

Kosher certification organizations — and CPG manufacturers as well — all realize that a kosher seal on a package is like a “silent salesman,” Horowitz said. And while certification organizations have a primary interest of ensuring products with the seal truly are kosher, there is a secondary goal of encouraging consumers to buy the products.

“Kosher: It may seem ancient, but the people doing it are modern and in the modern marketplace,” Horowitz said.

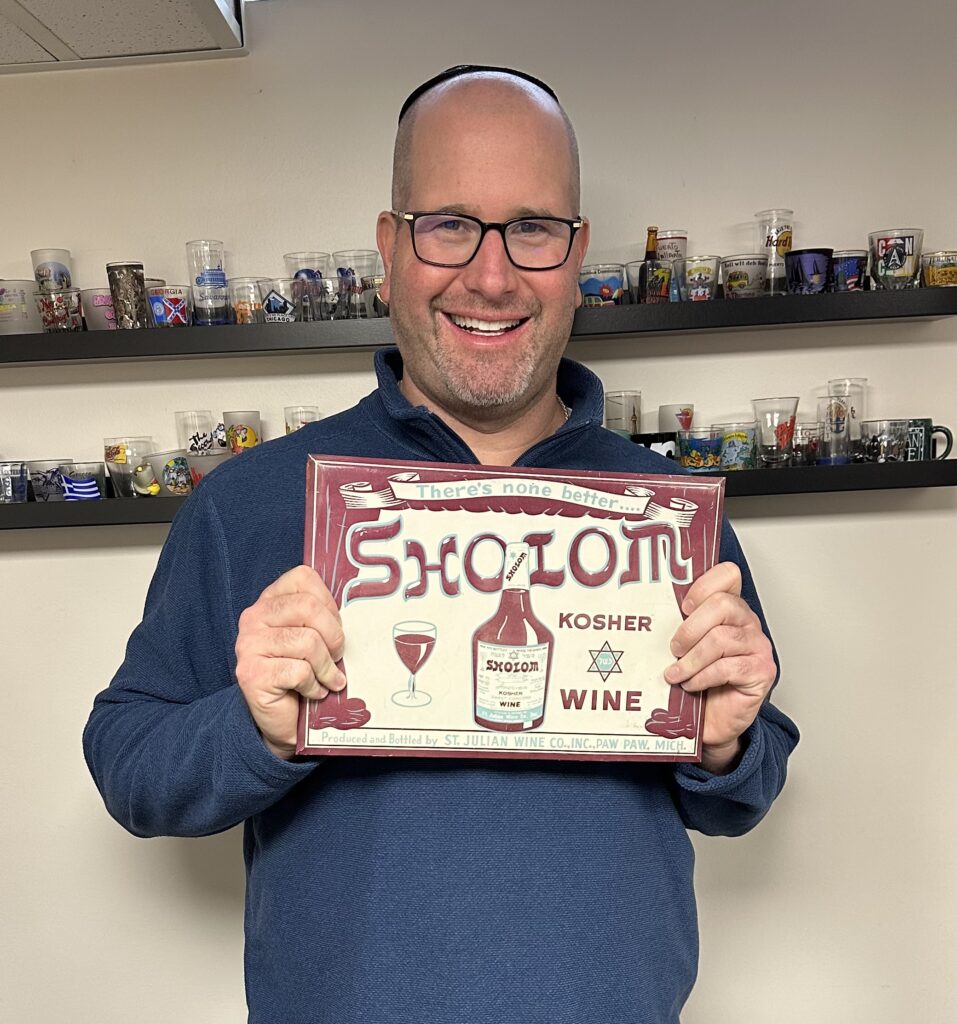

First introduced in the mid-1940s, Sholom has long been a popular offering from St. Julian Winery but has not been available since 2020. The long-time friend and rabbi the winery had worked with for years died. To be deemed kosher, wine must be made under the supervision of a rabbi, include only kosher ingredients and must be processed using equipment rabbinically certified to make kosher wines.

First introduced in the mid-1940s, Sholom has long been a popular offering from St. Julian Winery but has not been available since 2020. The long-time friend and rabbi the winery had worked with for years died. To be deemed kosher, wine must be made under the supervision of a rabbi, include only kosher ingredients and must be processed using equipment rabbinically certified to make kosher wines.

Kosher Michigan certifies thousands of products throughout North America, India and the Middle East. Kosher Michigan’s hekhsher (seal of approval) can be found on food products on supermarket shelves throughout North America.

Kosher Michigan certifies thousands of products throughout North America, India and the Middle East. Kosher Michigan’s hekhsher (seal of approval) can be found on food products on supermarket shelves throughout North America.

“Kosher Michigan is following the exact same kosher supervision process as the rabbis who previously certified Sholom wine for many decades, so there should be no concern that the highest kosher standards are not being followed,” said Miller.

“Kosher Michigan is following the exact same kosher supervision process as the rabbis who previously certified Sholom wine for many decades, so there should be no concern that the highest kosher standards are not being followed,” said Miller.