Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 914

Last month’s AKO conference brought together some 150 kashrus experts. Their primary motivation: making sure Klal Yisrael has kosher food to eat

The Jewish world today has hundreds of agencies making sure that all kinds of food is kosher, from the salmon off the Norwegian coast and Peruvian beef to French wines and Stella D’oro Swiss fudge cookies.

Once a year, the organizations get together for three days of camaraderie and enlightenment. From a business perspective, many of them are direct competitors, but at this conference, the focus is on what really motivates them: making sure people have kosher food to eat.

Under the umbrella of the Association of Kashrus Organizations (AKO), this year’s conference, held last month at the Delta by Marriott Hotel in Iselin, New Jersey, was certainly an eye-opener for me. I met people in kashrus organizations I’ve never heard of — Oregon Kosher, Top-K, Rhode Island Kosher — and from parts of the world, like South Bend, Amsterdam, and Panama, that I never even dreamed would have an organized hashgachah.

“People are always asking us, ‘What’s new?’ ” notes Rabbi Moshe Elefant, the chief operating officer of the OU Kosher. “What do you mean, ‘what’s new?’ There’s always something new happening in our industry.”

And so it was that I found myself striding into the hotel for the kashrus world’s biggest annual convention.

The Humans of the Kashrus Field

I came at the tail end of breakfast on a Tuesday morning, as kashrus experts from dozens of groups scurried to begin the day of presentations.

“Who gives the hechsher on this place?” I called out after them.

I’ve always been somewhat of a risk-taker and was grateful that the joke landed sturdily. It turns out that the caterer was Greenwald’s, which happened to have done my bar mitzvah some years back. The mini knishes I remember from that special night were nowhere in sight, but they did have quite a bash set-up.

Kashrus experts, it emerged, can have quite a sense of humor. One speaker, whose name I no longer remember, began his session, “I want to introduce to you a concept you may not know of — day and night.”

At one point I tweeted a photo of Chaikel Kaufman, who spoke on the topic of — and I quote — “Why not to use a travel agent.” Within minutes I got a text from the travel agent I’ve been using for years. “Did my boss speak well?”

Yes, Mr. Kaufman is apparently a travel agent of good standing.

“The first question I get when I meet people, and I tell them what I do is, ‘A travel agent? Who uses a travel agent today?’ ” Kaufman said. “And I don’t have a good answer for that.”

Mashgichim are frequent travelers, and Kaufman was there to give them some tips on how to make the most of their experience.

There were some fascinating moments as well. Rabbi Sholem Fishbane, the executive director of AKO, as well as the kashrus administrator of cRc Kosher (Chicago) announced three new initiatives to make people more kashrus aware. The first, which you may have heard of, is a series of videos and articles from the Kashrus Awareness website. The second is providing free kashrus consultation to summer camps for their camp kitchens, and the third is still under wraps and all information I received was off the record.

Lab Meat: The Modern Ben Pakuah

Modern science has promised us the miracle of meat grown in a laboratory, as a humane alternative to slaughter. But is it kosher?

Rav Moshe Heinemann, head of the Baltimore-based Star K certifying agency, delivered a shiur on the kashrus of lab-grown meat. The first patty made from cultured meat was created not even a decade ago, but Rav Heinemann found ample precedent for it in the rich body of halachah. A fundamental issue is whether the culture begins with cells taken from a living animal, and that seems to be “not kosher,” since we cannot eat meat that did not result from shechitah.

One part of his shiur was based on the sugya of ben pakuah — a living fetus discovered in the womb when the mother is slaughtered. Mid’Oraisa, the shechitah of the mother “covers” that of the fetus, and it would be permitted to eat it without a separate shechitah. But due to maris ayin, Chazal were concerned that onlookers would not realize this is a ben pakuah, and therefore decreed that it must have its own shechitah. However, if there were something very unusual about this animal — aside from it being a ben pakuah — then it would be permitted to eat it without shechitah. Everyone would realize that this was something unusual, and that would alert them that there might be some reason it was being eaten without shechitah.

What are examples of “unusual” things that allow the ben pakuah without shechitah? The Rema (Yoreh Dei’ah 13:2) gives an example of a ben pakuah whose hooves are not split. Rav Sherira Gaon permitted two calves that were ben pakuah to be served at his child’s wedding, arguing that the presence of two bnei pakuah at the same time was unusual enough to qualify for this exception. Rav Heinemann said that he knows of a ben pakuah that was born without a tail — a prime example of a double oddity. The lack of a tail tremendously affected the animal’s ability to disperse the hundreds of flies that are attracted to its skin and Rav Heinemann thought that was peculiar enough to be another example of one that can be eaten without shechitah.

Based on all this, Rav Heinemann proposed that if the cultured meat were labeled as coming from a ben pakuah, that would also be considered unusual enough to permit its cells (and meat) without shechitah, and the meat could be cultured from it.

Assuming we overcame the shechitah issue, would the cultured meat be considered pareve?

“If it looks like meat, it tastes like meat, it smells like meat, it’s meat,” Rav Heinemann declared. “Fleishigs.”

Kosher Raspberries: Coming Through

Could raspberries soon be rejoining the pies and cocktails of the Jewish fruit bowl? They’ve been banished for many years due to insect infestation, but a new technology could make them grow as bug-free as greenhouse cabbage, according to Rabbi Lazer Fischer of Cincinnati Kosher.

Vertical farming, Rabbi Fischer said in his session, arose from scientists’ fears that the world’s existing arable land will no longer be able to feed the global population by 2050.

“You know why?” he asked. “Because the scientists say that the world has issues. The globe as we know it is in danger due to global warming, over-farming, and soil erosion.”

To solve this, environmentalists invented vertical farming.

He took attendees through a virtual tour of 80 Acres Farms, located on the outskirts of his home city of Cincinnati. The facility produces over 1.6 million plants at any given time. A dark room contains hundreds of peat mosses, each containing a single seed ensconced in dirt. Every few days it gets transferred to an increasingly larger “grow zone” to give it more space to grow. Lights of blue and red, which together emit a purplish tinge, are shone on the plants. These are the only two colors that have an effect on plants, Rabbi Fischer explained.

80 Acres Farms has designed its facility to filter all venues that could serve as conduits for bugs — humans, air, and water — eliminating the odds that insects are in the produce. How they do it is a commercial secret, though they have let the kashrus agency in on the secret. There is minimal contact with humans and air, and water consumption is 97 percent less than the 70 liters per plant per year used by traditional farming.

For now, vertical farming is used for leafy vegetables like lettuce, but 80 Acres is experimenting with strawberries and raspberries.

“It’s not a given that if it’s a vertical farm, then it is bug free,” Rabbi Fischer said. “But there is a very good chance that you could get to that point if the facility is designed properly and has proper oversight.”

No Compromises: Are We Back to the Bad Old Days?

The glut of kosher food, lamented Rabbi Moshe Elefant, the chief operating officer of OU Kosher, has made many Yidden complacent that if “everyone eats” a food then it must be kosher. This threatens to take the community back to the bad old days when anything went.

“When we were younger, we ate just about everything,” he said. “If it looked kosher or it sounded kosher, we ate it. Then, the world got better. But what I’m seeing today is that people are going back to deciding based on assumptions and guesses. Did the proliferation of ‘lists’ of approved items — such as the liquor lists or Slurpee lists — create an environment in which people are satisfied with saying that a food is probably okay?”

He pointed to the Grey Goose vodka controversy last year, in which it was suggested that the spirit contained grape-based alcohol (stam yayin), rendering it not kosher. While it ultimately turned out to be fine, the scare set Rabbi Elefant thinking — even if one day it is okay, what stops Grey Goose from mixing in grape alcohol some other day? Yet people were not worried and went right back to sipping their vodka without hashgachah.

Rabbi Elefant has a plethora of similar stories: discovering that Southern Comfort, a once-popular drink in the heimish community, contained grape-based alcohol; finding out that After Eight Dinner Mints, produced by a British company, and eaten with tea by London’s Jewish community every Friday night after the seudah, had butter oil mixed in, making it milchigs.

He said that the time has come for this attitude to change. He recalled how many years ago he told Rav Chaim Yisroel Belsky ztz”l, one of the OU’s poskim, that he was hesitant to inform companies under his supervision that wholesale changes may be coming. How can we insist that they change from what we’ve always allowed them to do?

“Anyone who has that attitude,” Rav Belsky answered firmly, “should not be working in kashrus. We must always be checking and reevaluating ourselves.”

Mooo, You’re on: Candid Camera

The recent Covid pandemic hung heavily over the conference, which was dedicated in memory of two kashrus giants who were niftar during the outbreak — Rabbi Dr. Zecharia Senter, the founder and rabbinic director of Kof-K, and Rav Don Yoel Levy, the rabbinic director of the OK. In addition, many of the sessions were devoted to lessons learned from the virus years.

Can cameras, for example, replace human oversight? The experience of the past years has proved to be a mixed bag, said Rabbi Moshe Gutnick, from the kashrus authority of Australia and New Zealand.

Rabbi Gutnick spoke about the use of cameras in the production of chalav Yisrael. Cameras have been used extensively during the Covid pandemic, but they have turned out not to be as foolproof as they initially thought.

“There are many things that you can’t see,” Rabbi Gutnick declared, “You have to be careful that you weren’t hoodwinked when using a camera.”

So what are cameras good for? Rabbi Gutnick explained that they are good as a hiddur, or if you need a specific task to verify.

He then offered a pilpul on the effect witnesses have: In some cases, they create the event, such as at a wedding. In other cases, they merely provide proof of an occurrence, such as with monetary transactions. When it comes to chalav Yisrael milk production, Rabbi Gutnick said, one could argue that a mashgiach watching the milking on a camera would be sufficient. But on the other hand, the Chasam Sofer says that the rabbinic decree prohibiting chalav akum was given for a reason that was not revealed. According to this, having a camera would not suffice, since perhaps that “other reason” requires a human physically observing the milking process. He further noted that all would agree that a Jew watching a camera would not be enough to create gevinas Yisrael (for cheese).

Other issues with cameras are that (a) they are technological, which means that they are bound to fail and break every so often, and (b) it is hard for a mashgiach to stare at a screen for extended periods of time.

“The fact of the matter is,” Rabbi Gutnick said, “watching a long row of cows walk to be milked is very boring, and it’s easy for a mashgiach looking at a monitor to fall asleep or get distracted.”

The ideal mashgiach is someone who pays attention to what is happening and reports back to the rabbinic supervisor.

One person who knew little about farms or animals was once serving as a last-minute substitute mashgiach at a dairy plant, Rabbi Gutnick recalled. He called his rabbinic supervisor, breathlessly yelling into the phone, “They’re milking a horse! They’re milking a horse!”

The kashrus agency sent someone down to check out what was happening and discovered a herd of black and white cows, with the mashgiach screaming “There’s the horse!” as he pointed at the one brown jersey cow mixed into the herd.

“We had to explain to him that a brown cow is a cow, not a horse,” Rabbi Gutnick said. “But at least that mashgiach was paying attention.”

Ask and Answer: Rav Dovid Cohen

One of the most fascinating sessions was a Q&A with Rav Dovid Cohen, the rav of Congregation Gvul Yaavetz and a prominent posek in Flatbush. Laden with wisdom and delivered with wit, he began with the pronouncement that a shiur must begin with a milsa d’bedichesa — a joke.

“Three years ago,” he began, “when Rabbi Sholem Fishbane asked me to speak at this conference, I said, ‘Everything is fine, I just have to check out the kashrus.’ ”

Rav Cohen was asked whether a kashrus organization may hire a mashgiach currently employed by a different agency.

He prefaced his answer with a fascinating, behind-the-curtains look at how rabbanim rule on halachah. The mesorah of Lita, from Rav Chaim Volozhiner to Rav Moshe Feinstein, was to study the sugya and issue a psak based on their understanding of its conclusion, even if it differed with Rishonim. The mesorah in Hungary, though, was to cite all opinions, and then rule based on the majority.

As to the question itself, Rav Cohen said that all such queries — hiring a chef away from a different caterer, offering a higher salary for a cleaning lady, or hiring a rebbi who teaches at a different mosad — have the same answer. One may not directly ask the employee to leave his place of work, but one may advertise in a place that the person will notice it and call him on his own.

“This is the minhag ha’olam, and this is the acceptable psak,” Rav Cohen declared.

Some of the questions dealt with thorny issues that had no clear answer. What is the kashrus agency’s responsibility regarding the “ambience” of a facility where it provides a hechsher? One kashrus organization recalled having a Christian symbol at an event, and another recoiled at having to provide a hechsher at an event that featured inappropriate activity.

“I don’t know,” the rav responded. “It’s a judgmental thing.”

If there is pritzus, he said he would advise against it, but if it’s primarily a staid affair that also has some objectionable content, then he would permit it. But he emphasized the responsibility kashrus organizations have to save uninformed Yidden from eating treif.

What should a kashrus organization do if a mashgiach it employs is credibly accused of withholding a get from his wife or not paying child support? These things are a massive chillul Hashem, Rav Cohen responded.

“You are part of Klal Yisrael, and Klal Yisrael must help free an agunah,” he said. “I’m not saying to fire him yesterday. But you should replace him. Tell him that we are going to look for another mashgiach. You’ll probably find someone else.”

Are there grounds to be lenient when it comes to kashrus issues in retirement homes? Rav Cohen said yes, noting that a common expression in the Shulchan Aruch is that “a sick or elderly person is allowed.” He said, “It doesn’t say that the elderly people are sick, it says sick or old.”

I left the conference with a new appreciation of the Mishnah in Avos, “Hafoch bah v’hafoch bah, d’kula bah.” Turn the Torah around and examine it from every angle, because if you do so, you will discover that it addresses every issue and every question.

Tossing Rivalry to the Winds

One of Rabbi Moshe Reich’s early assignments after coming to work at the Kof-K kashrus agency was to take a senior Pepsi official out for lunch. It was approximately 13 years ago, and the soft drink giant’s vice president of operations was coming to the Kof-K headquarters in Teaneck.

Pepsi was the agency’s client, and Kof-K CEO Rabbi Dr. Zechariah Senter tasked Rabbi Reich with handling the executive. Rabbi Reich searched for an upscale kosher restaurant and took Rabbi Senter and the executive there.

As they were seated, a waitress came over to take their order.

“I’ll take a Diet Pepsi,” said Mr. Pepsi.

“I’m sorry, we don’t carry Pepsi,” she responded. “Can I get you a Coke?”

“No,” he said. “I’ll just have some water.”

Rabbi Reich, mortified for not thinking of this simple hitch, questioned him: Would he really not drink a Coke?

“I don’t understand, Rabbi,” Sherman replied in astonishment. “You’re from the Kof-K, would you eat from the OU?”

“Sure,” Rabbi Reich said.

Sherman stared at him in shock. He then told him that he had once taken his son to a game at Yankee Stadium, where Coke has the franchise. He told his son beforehand that there would be no drinks at the game. However, in middle of the game, his son begged for a drink.

“You know the rules, we only drink Pepsi,” he told his son. “I’d rather buy a beer and get arrested than drink a Coke.”

“That,” Rabbi Reich tells me, “is what real competition looks like in the outside world.”

The Jewish version of competition was on intense display at the recent Association of Kashrus Organizations conference, where 150 representatives from 75 kashrus agencies hobnobbed, traded tales from the field, and swapped ideas.

Rabbi Reich, who organized the confab, said it was “the largest conference AKO ever had.”

“I appreciate that Mishpacha is dedicating time for this, because I don’t think the kashrus world realizes how much we actually work together,” he said.

As a symbol of the unity, the conference was dedicated in memory of Rav Senter and Rav Don Yoel Levy. Rabbi Levy was niftar on Acharon shel Pesach at the height of Covid and had a quick levayah; Rabbi Senter was niftar a year later to the day and also had a rushed levayah to make a flight to Eretz Yisrael for kevurah.

Rabbi Ari Senter, the current director of kashrus standards at Kof-K, wanted to do something for them, and he worked with AKO to dedicate the conference in their memories. He asked each kashrus organization attending to take one of the ArtScroll Shas’s seventy-some volumes so they could make a siyum haShas, which took place alongside a hachnassas sefer Torah.

Rabbi Senter of Kof-K spoke about Rabbi Don Yoel Levy of OK, and Rabbi Meir Fogelman, Rabbi Levy’s son-in-law, paid tribute to the late Rabbi Senter.

“Everyone thought we made a mistake,” Rabbi Reich said. “People were asking, ‘Why is Rabbi Senter talking about Rabbi Levy, shouldn’t it be the opposite?’ But we told everyone we did this on purpose.”

This was Rabbi Reich’s third stint as AKO conference organizer.

“I felt like I was making a chasunah but I didn’t have to pay for it,” he joked. “I had to make a seating chart, trying to make sure that people who have things in common sit near each other.”

His first conference was in 2018, followed by another in 2020, which ran alongside the Siyum HaShas on daf yomi on January 1. The AKO organization was established in 1985 but reached its current format two decades ago. Responsibility for the annual conventions rotates among several agencies.

The current one was originally scheduled for the end of December, but with the Omicron variant spreading, Rabbi Senter felt it would be a chillul Hashem if there was a Covid outbreak because of it, so it was canceled.

Aside from the US and Canada, four other countries were represented — South Africa, Britain, Israel, and Australia. Several heimishe agencies attended for the first time. Rav Dovid Cohen was there as a guest the entire time, making himself available to answer questions privately.

One priority of conference organizers was the smaller kashrus agencies, since the Kof-K regularly travels to their cities to train in their mashgichim. There are seven major kashrus certifiers in North America — OU, OK, Star-K, Kof-K, and cRc in the United States, and COR in Ontario and MK in Montreal — and some five dozen smaller ones spread out throughout the country, from AKC in Atlanta to OVK in St. Louis to the Rabbinic Council of California. The conference held a special session on how to certify kashrus properly utilizing just one or two staffers.

Reflecting on the conference, Rabbi Reich said, “You had the new guard and the old guard getting together, having that handshake and getting to know each other. It was a tremendous display of achdus. I’m still getting messages from people who say they are still riding the coattails of the conference. That should be the ultimate message.”

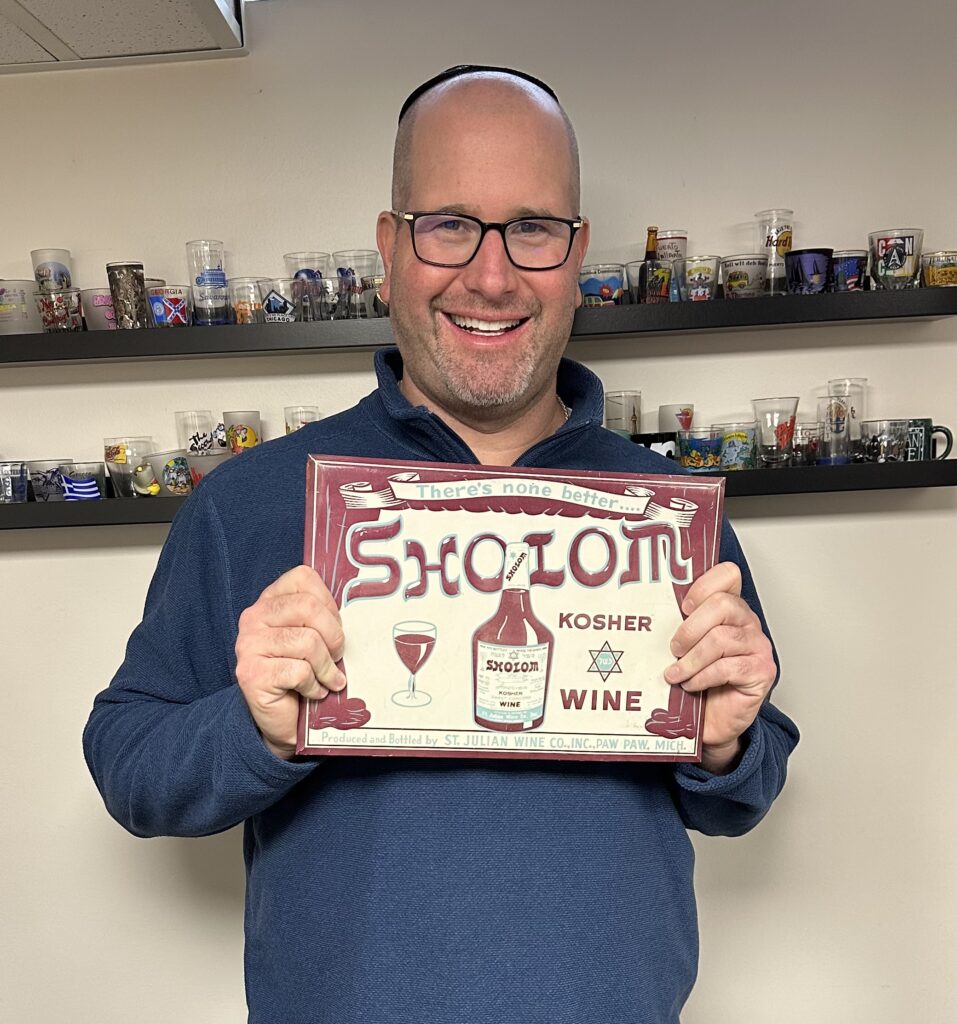

First introduced in the mid-1940s, Sholom has long been a popular offering from St. Julian Winery but has not been available since 2020. The long-time friend and rabbi the winery had worked with for years died. To be deemed kosher, wine must be made under the supervision of a rabbi, include only kosher ingredients and must be processed using equipment rabbinically certified to make kosher wines.

First introduced in the mid-1940s, Sholom has long been a popular offering from St. Julian Winery but has not been available since 2020. The long-time friend and rabbi the winery had worked with for years died. To be deemed kosher, wine must be made under the supervision of a rabbi, include only kosher ingredients and must be processed using equipment rabbinically certified to make kosher wines.

Kosher Michigan certifies thousands of products throughout North America, India and the Middle East. Kosher Michigan’s hekhsher (seal of approval) can be found on food products on supermarket shelves throughout North America.

Kosher Michigan certifies thousands of products throughout North America, India and the Middle East. Kosher Michigan’s hekhsher (seal of approval) can be found on food products on supermarket shelves throughout North America.

“Kosher Michigan is following the exact same kosher supervision process as the rabbis who previously certified Sholom wine for many decades, so there should be no concern that the highest kosher standards are not being followed,” said Miller.

“Kosher Michigan is following the exact same kosher supervision process as the rabbis who previously certified Sholom wine for many decades, so there should be no concern that the highest kosher standards are not being followed,” said Miller.