From Treif to Treat: How Oreos, Coke and Jell-O Became Kosher

‘Kosher USA’ is a detailed account of the scientific and business-related aspects of the history of kashrut, including the battles to allow observant Jews to enjoy forbidden favorites.

By Professor David Kraemer

Haaretz Daily

“Kosher USA: How Coke Became Kosher and Other Tales of Modern Food,” by Roger Horowitz, Columbia University Press, 320 pp., $35

Not so very long ago, obtaining kosher food was a relatively simple affair. The food you ate was available in your garden or local market. Ingredients were seasonal, simple and few. There were no preservatives as such, so durable foods could be stored; perishable foods might be smoked, pickled or salted. In general, you acquired, prepared and ate your food all within a day or two.

By virtue of the transparency of such markets, there were no kosher signs or organizations granting formal kashrut certification; your meat had to be slaughtered by someone who was approved by the local rabbi, but nothing more was demanded.

Kosher USA Book – Roger Horowitz

Then, in the 20th century, kashrut changed forever. Increasingly, food production was industrialized, the sources of ingredients often distant and obscure. Whereas in earlier times you could see the grain or potato or onion you were buying in the market bin, and you knew what kind of fat you were using to fry or flavor your food – now everything was prepackaged, and ingredient lists, filled with chemical names and technical terms, did an inadequate job of allowing you to separate the kosher from the non-kosher. Only professional rabbinic overseers, increasingly employed by kashrut organizations, had the expertise to determine what you were permitted to buy. Kosher symbols on packaging became essential to the observant community.

Nowhere did this process occur earlier or more completely than in the United States, which also happened to be, and continues to be, home to one of the largest Jewish communities on Earth. The experience of this community, therefore, is of extraordinary interest to anyone interested in modern Judaism. Thus, Roger Horowitz’s “Kosher USA: How Coke Became Kosher and Other Tales of Modern Food” is a rich account of its path through the transition just described. There is no prior book that documents the history of kashrut in America with such detail (though Sue Fishkoff’s “Kosher Nation” covers some of the same territory from a different perspective).

The story Horowitz’s book tells is a fascinating one, and he does a masterful job sleuthing and documenting the development of kashrut and the kosher food industry from the major waves of Jewish immigration in the early 20th century through the status quo of the early 21st.

After a cursory history of the origins and development of kashrut from antiquity, Horowitz begins his account with a discussion of the complications and controversies regarding the kashrut of Coca-Cola — not merely a soft drink but a symbol of American culture and power.

Recalling the important place Coke had on his seder table when he was a child, Horowitz reports that when he looked into the story of its kashrut, he quickly discovered that the standard account — according to which Atlanta Rabbi Tobias Geffen persuaded the company, in 1934-35, to change the drink’s formula to make it acceptable — is full of holes. He recounts that the controversy over Coke’s kashrut began before Geffen got involved, and continued until the late 1950s.

So what was the full story? The ingredient that rendered Coca-Cola — and many other processed foods — a kashrut problem was glycerin, derived primarily from the fats of unkosher animals. An earlier rabbi had declared Coke kosher, but didn’t understand the origins of glycerin. Geffen ruled that such glycerin was unacceptable, even in minute quantities, but he persuaded Coca-Cola to use glycerin of vegetable origin, and thus saved Coke for the kosher table.

Coca-Cola. Author Horowitz remembered how important it was at the seder meal and looked into the story of its kashrut. Bloomberg

However, an Orthodox chemist by the name of Abraham Goldstein, whom Horowitz views as the protagonist of the story, demanded greater stringency, insisting that Coke’s sourcing of glycerin was still suspect. He challenged the expertise of rabbis in rendering such opinions, insisting that, in the modern industrial context, only someone trained in chemistry, like himself, could make an educated judgment.

Goldstein was relentless in promoting this position, championing it through the increasingly popular publication, the “Kosher Food Guide,” put out by the Organized Kashrut Laboratories (aka OK Labs). Ultimately, it was his approach that prevailed, making scientific considerations central to kashrut decisions until the present day. Coke “remained” kosher by changing its formula to conform with Goldstein’s standards.

Glycerin wasn’t the only ingredient that created such problems. The kashrut of a variety of foods popular in the 1950s and ’60s, such as Jell-O and marshmallows, was subject to question on account of the gelatin that was essential to their manufacture. Gelatin might be extracted from various sources, kosher and unkosher, and earlier rabbinic authorities had mostly given it a green light, whatever its source, on account of the radical transformation of the original substance in the process of making gelatin. But during the period in question, gelatin came to be made primarily from collagen originating in pigs. This, Horowitz writes, was a “ticking time bomb,” because kosher consumers would never accept an ingredient with such a source, no matter how changed it might be.

Partly as a response to this reality, the rabbinic establishment came to accept the more restrictive view championed by Goldstein with respect to ingredients with unkosher sources. However, Horowitz perceptively writes, “such a dramatic change indicates that something more than a rethinking of kosher law was at work… something that closely touched basic issues of Jewish identity in postwar America.”

What was this “something?” In Horowitz’s view, the “Orthodox were becoming more stringent to ward off the challenge posed by Conservative Judaism.”

This may well be part of the explanation. But then why admit the crucial place of science in questions of kashrut, particularly since attention to science and other modern disciplines was part of what characterized the approach of Conservative Judaism in the first place? Besides, the rightward direction of kashrut practice was part of a much larger rightward inclination in Orthodoxy, as amply documented by Samuel Heilman in “Sliding to the Right.”

What was it about life after the Holocaust that might have influenced these trends? What about changes in the demographics of Jews in the U.S.? About what was happening in religious practice in Israel and how Israel affected the Diaspora? There is a considerable literature on all of these questions, yet Horowitz seems not to be familiar with it; in any case, it doesn’t influence his analysis, and this is an unfortunate weakness.\

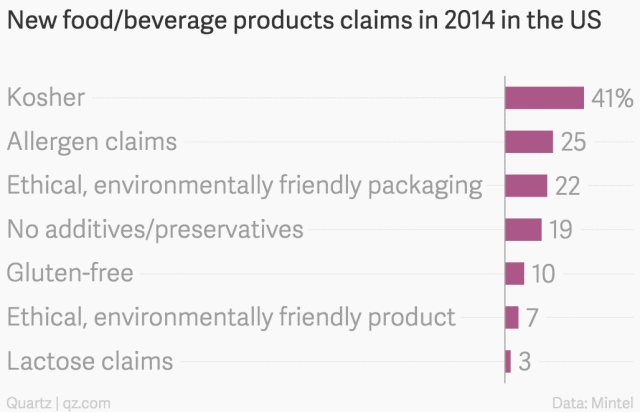

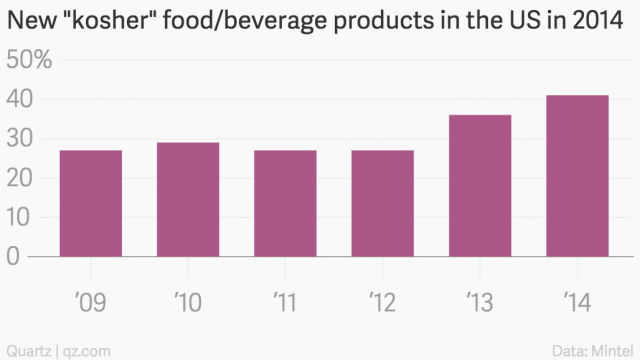

One of the great strengths of the book is Horowitz’s discussions of business considerations in shaping the growth or shrinkage of the market for kosher foods (Horowitz, as a historian of American business, is the person to write this history). Energizing growth were such factors as the greater efficiency of manufacturing a single product for both observant Jewish and other markets rather than having different production lines — which led, for example, to the decision to make Oreos kosher so that they could be used in Cookies and Cream ice cream. This was the answer to many a Jewish child’s dream, as before they could only long for the popular but forbidden cookie!

Also crucial to successes enjoyed by kosher food manufacturers was the perception among gentiles that a kashrut mark was a sign of purity and quality, making kosher products more desirable. Kosher manufacturers consciously sought to take advantage of this broader market, and their advertising often targeted non-Jews directly. Hebrew National hot dogs, sold in super markets and not just kosher butcher shops, and advertised as “answer[ing] to a higher authority,” is perhaps the best example of this phenomenon.

Horowitz’s discussion of kosher wines is particularly well done, weaving a story of both a growing and a shrinking market – a trajectory that, in his view, leaves observant Jews in a more marginal position than is commonly understood. Horowitz begins by recounting the growth of the market for sweet kosher wine — made by Manischewitz — among poorer minorities, who appreciated its lower cost and sweeter taste.

Correctly sensing a potential boon to its sales, the company enthusiastically promoted its product to this market. But — in some measure due to racist attitudes — Jews began to eschew the wine, and even led some to question its kashrut. Most Jews turned to other kosher wines, and, with the development of more refined tastes, to drier wines. But the need, in America, for wine that was mevushal (“boiled”) — so that non-Jews would be permitted to serve it at Jewish affairs (in general, the touch of a non-Jew renders kosher wine impermissible, but Jewish law permits it if is mevushal) — meant that the quality of kosher wines was compromised.

Unlike many other kosher products, kosher wine never developed a reputation for quality, and the market for such wines remains overwhelmingly limited to observant Jews. The final chapters of the book are devoted to the production and sale of kosher meat. Again, Horowitz offers a fine history of kosher slaughter in the U.S., along with the kosher marketplace and its changes. He describes how kosher slaughterhouses were originally a local affair, located, for example, on both the far west and far east sides of Manhattan (the meat-packing district and the present property of the United Nations).

Following World War II, when meat production was increasingly industrialized, moving to massive plants in the Midwest, maintaining kashrut presented a problem: To assure that the blood could still be extracted from the flesh through salting, carcasses had to be washed every three days while being transported to local markets. This was common practice in the 1950s and later, until the slaughtering plants began salting and packaging the meat themselves.

However, solving such problems created other issues, as animals came to be treated as mere meat-producing commodities, and cruelty to animals (in how they are raised and slaughtered) has led to disgust and condemnation. This is not problem unique to kosher meat, but it is particularly difficult to ameliorate, as kosher slaughter does not permit stunning before the knife is put to the neck.

Horowitz offers a fine history of both the ethical problems involved in kosher slaughter and the development of organizations that seek to improve conditions in the slaughterhouses. As a journalistic history of kashrut in America, Horowitz’s book is to be recommended. But its journalistic quality is both a strength and a weakness. Horowitz is a reporter who does superb research, and, as a business historian, he is very attentive to the dynamics of the market. But the market is never the full story, and his reportage is rarely accompanied by a fuller analysis. He almost never incorporates consideration of sociological or social-religious factors, and when he does, his analysis is cursory, at best.

There are, for this reader, other weaknesses that should also be mentioned. Seeking to render his discussion more accessible, Horowitz frequently cites his experiences with his own family and neighborhood. But his virtually exclusive reference to the life of Jews on the Upper West Side of Manhattan makes both the author and the neighborhood seem parochial, and leaves the reader asking, “What about the rest of Jewish America?”

Finally, I have some question about the author’s Hebraic proficiency: his translation of b’lios as “taste” (as opposed to “[material that is] absorbed”) is incorrect, if serviceable for his purposes, and he repeatedly — and incorrectly — refers to the “ethical kosher” organization Magen Tzedek as Magden Tzedek, an awkward error.

Despite these problems, I strongly recommend Horowitz’s books to anyone interested in the topic. His history is superb, and his work will allow others to offer their own analyses and interpretations. He lays a very strong foundation here, and for that he is to be commended.

David Kraemer is a professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary and the author of “Jewish Eating and Identity Through the Ages.”

read more: http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/books/.premium-1.722415